The religion of the Etruscans, the civilization which flourished from the 8th to 3rd century BCE in central Italy, has, like many other features of the culture, long been overshadowed by that of its Greek contemporaries and Roman conquerors. The polytheistic Etruscans had their own unique and distinct pantheon and practices, chief amongst which were augury (reading omens from birds and lightning strikes) and haruspicy (examining the entrails of sacrificed animals to divine future events). That the Etruscans were particularly pious and preoccupied with destiny, fate, and how to affect it positively was noted by ancient authors such as Livy, who described them as 'a nation devoted beyond all others to religious rites' (Haynes, 268). Etruscan Religion would go on to influence the Romans, who readily adopted many Etruscan figures and rituals, especially those concerned with divination.

Problems of Interpretation

The Etruscan gods have long been seen by some as mere equivalents of their Greek and Roman counterparts, starting with Latin writers such as Cicero and Seneca, and while there may be some similarities in certain deities across the three cultures, it is not always the case. One of the problems for historians of Etruscan religion is that Roman writers are one of the chief sources of information from antiquity, and although they often quoted from now lost texts, their labelling and descriptions are not always accurate. In addition, Roman writers are sometimes biased in their descriptions, anxious as they were to minimise the contribution of the Etruscans to Roman culture. Additional sources which help redress this imbalance include inscriptions - especially on sarcophagi, votive offerings and bronze mirrors, and pictorial evidence such as tomb wall paintings and funerary sculpture made by the Etruscans themselves. Given these difficulties and the general lack of longer written texts on the subject, any summary of the Etruscan religion must, for the moment, remain incomplete.

Etruscan Gods

As with many other ancient cultures, the Etruscans had gods for those important places, objects, ideas, and events which were thought to affect or control everyday life. At the head of the Pantheon was Tin (aka Tinia or Tina); Aita the god of the Underworld, Calu was god of Death, Fufluns of wine, Nortai of destiny, Selvans god of fields, Thanur the goddess of birth, Tivr (aka Tiur) was the goddess of the Moon, Usil the Sun god, and Uni was perhaps the queen of the gods and most important goddess. The national Etruscan god seems to have been Veltha (aka Veltune or Voltumna) who was closely associated with vegetation.

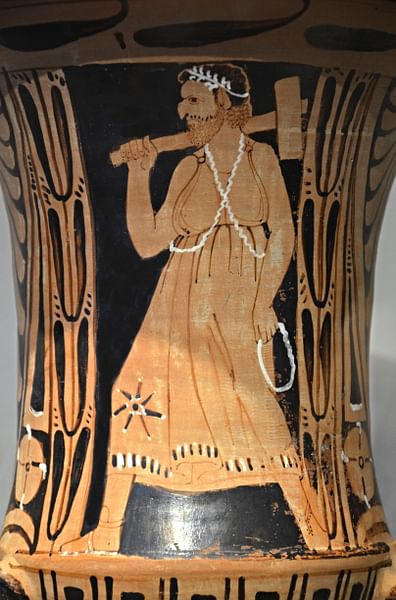

Lesser divine figures include the 12 advisors to the gods, the dii consentes, who had a reputation of acting without mercy; young female figures similar to the Greek nymphs known as Lasa; winged females known as Vanth who seem to be messengers of death; and various heroes, notably Hercules and the Tinas Cliniar (twin sons of Tin and equivalent to the Greek Dioscuri). One figure who, perhaps not surprisingly, appears frequently in Etruscan tomb wall paintings is Charu (or Charun) who, unlike the Greek version of the ferryman who transports souls to to the Underworld, has a hammer and key, presumably in his role as gatekeeper to the next world (hammers were used to move the heavy bar of city gates).

By the 5th century BCE, many Etruscan gods became assimilated to Greek ones, a process seen in art objects (e.g. black-figure pottery and mirrors) where images of the Olympian gods are given Etruscan names in added inscriptions. Thus Zeus is Tin, Uni is Hera, Aita Hades, Turan is Aphrodite, Fufluns Dionysos, and so on. It also seems that earlier Etruscan gods were somewhat faceless deities while the Greek influence increased their 'humanisation,' at least in art.

Priests & the Etrusca Disciplina

Priests (cepen) consulted the collection of sacred texts known as the Etrusca disciplina. This corpus of literature is now lost (perhaps deliberately so by early Christians), but it is described and referred to by Roman writers. The three main sections detail the reading of omens (for example, the flights of birds and lightning strikes), the prediction of future events by consulting animal entrails following their sacrifice (the liver being an especially valued object of examination), and general rituals to be observed so as to gain favour from the gods. Other matters covered include instructions for founding a new settlement, procedures for placing city gates, temples and altars, and guidance for farmers. The Etruscans believed that all this wealth of information came from a divine source, two in fact: the wise infant Tages and grandson of Tin, who miraculously appeared from a field in Tarquinia while it was being ploughed, and the nymph Vegoia (Vecui). These two figures revealed to the early Etruscan leaders the proper religious procedures expected by the gods and the handy tricks of divination.

Priests were predominantly males, but there is limited evidence that some women may have had a role in ceremonies. They learnt their subject in university-type institutions of training with that at Tarquinia being particularly renowned. Priests would also have had important roles in government as there was no separation of religion from the state, or from any other branch of the human condition either, for that matter. In this context, the mention in inscriptions that sometimes priests were elected is more understandable.

Augurs, the readers of signs, were identified by the staff with a coiled top which they carried, the lituus, and their dress: a long robe, sheepskin jacket, and conical peaked hat. Priests are depicted as clean-shaven while trainees are not. Their knowledge of reading entrails was a deep one as a bronze votive liver from Piacenza illustrates. The piece is divided into an incredible 40 sections and inscribed with 28 gods, indicating the complexity of the subject and exactly which god was likely in need of offerings depending where any imperfection of the liver might occur. Those priests who interpreted birds' flight or thunder and lightning had to possess a similar mind map as just which part of the sky these phenomena occurred in, the direction, the type of thunder, lightning or bird (owls and crows croaking were especially inauspicious), and the time and date would all indicate which of the thunder and sky gods was angry or pleased that day.

The Etruscan preoccupation with knowing the future was not because they thought they could influence it for they believed that everything is already predetermined. This abandonment of humanity's possibility to affect future events distinguishes it from contemporary religions such as the Greek. At best, terrible events could only be identified and postponed, perhaps diminished a little in severity, or even directed towards others, but they could not be avoided.

Religious Practices

The focus of Etruscan religious ceremonies was animal sacrifices, which took two forms. The first was to burn the offering in honour of the gods who dwelt in the heavens, while the second form was to honour underworld deities by offering the blood of the animal sacrificed. This was done by allowing it to drain into a special conduit which ran into the ground beside the altar. Similar libations were made in tombs when burials were made. The sacred precinct was also the scene of food offerings, prayers and hymn singing to a musical accompaniment.

Votive offerings were made by all classes and both sexes as inscriptions on them by the offerer attest. These could take the form of small terracotta figurines of animals and humans (including individual body parts), vases, bronze statuettes, and anything else the offerer considered valuable enough to win the gods' favour. Offerings were left not only at temples but also at natural spots considered sacred such as rivers, springs, caves, and mountains. Offerings were left in tombs, too, to help the deceased in the next life and ensure the gods looked favourably on them.

Another method to attract the favour of the gods and avoid personal calamities was to wear amulets or charms, especially for children. The most common, the bullae, were small lentil-shaped capsules worn on a string around the neck. Similarly, one could do the opposite and inflict harm on others by preparing curse tablets or tiny figurines with their hands tied behind their backs which were sometimes thrown into wells.

Etruscan Temples

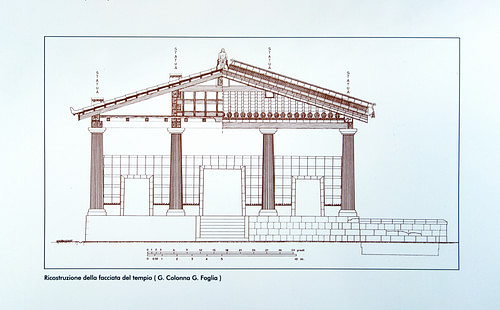

The earliest Etruscan sacred spaces had no architecture to speak of, merely being an outdoor area defined as sacred with an altar where rites were performed. Some areas had a rectangular podium from where omens could be observed. Over time, buildings, probably only of wood and thatch at first, were erected and the first Etruscan stone temple appears at Veii c. 600 BCE.

Etruscan temple architecture has been difficult to reconstruct because of the lack of surviving examples. The Roman architect and writer Vitruvius describes a distinct 'Tuscan temple' type with a columned portico and three small chambers at the rear interior, but evidence points to a more varied reality. One of the best documented Etruscan temples is the c. 510 BCE Portonaccio Temple at Veii. With a front stepped-entrance, columned veranda, side entrance, and three-part cella, it does match Vitruvius' description. The roof was decorated with life-size figure sculpture made in terracotta, a figure of a striding Apollo survives. The temple was perhaps dedicated to Menrva (the Etruscan version of Athena/Minerva). As in Greek temples, the actual altar and place of religious ceremonies remained outside the temple itself.

All towns had sacred precincts and usually three temples, considered the most auspicious number. Some sanctuaries attracted pilgrims from across Etruria, even from abroad and the most famous were the large Temple at Pyrgi near Cerveteri and the Fanum Voltumnae sanctuary, possibly near Orvieto (exact location as yet unknown). At the latter elders of the various Etruscan cities met annually for the most important religious festival in the Etruscan calendar.

Etruscan Burial Practices

The burial practices of the Etruscans were by no means uniform across Etruria or even over time. A general preference for cremation eventually gave way to inhumation, but some sites were slower to change. Simpler stone cavities with a jar of the deceased's ashes (which at Chiusi have lids carved as figures) and a few daily objects gave way to larger stone tombs enclosed in tumuli or, even later, free-standing buildings often set in orderly rows. These latter 7th-5th-century tumuli and block tombs had more impressive goods buried with the uncremated remains of the dead (one or two persons) such as jewellery, dinner service sets, and even chariots. The presence of these objects is an indicator of the Etruscan belief in the afterlife which they considered a continuation of the person's life in this world, much like the ancient Egyptians. There is no evidence the Etruscans believed in any sort of punishment in the afterlife, and if art is to be considered, then it would seem that the hereafter was, starting with a family reunion, an endless round of pleasant banquets, games, dancing, and music.

The walls of the tombs of the elite were painted with colourful and lively scenes from mythology, religious practices and Etruscan daily life, especially banquets and dancing. The 4th-century BCE Francois Tomb at Vulci is often cited as the finest example. Ornate sarcophagi become more common from the 4th century BCE, while in the Hellenistic period cremations return alongside inhumations, this time in terracotta boxes with a large painted figure sculpture on the lid depicting the departed. Many tombs of this period were in use for several generations.

Influence on the Romans

The Etruscans were not the first civilization which endeavoured to interpret signs in entrails and celestial phenomena or create calendars of significant events, as the ancient Babylonians and Hittites were noted for their expertise in this field before them. Nor would the Etruscans be the last, as the Romans adopted the practice too, along with other features of Etruscan religion such as rituals for establishing new towns and dividing territories, something they would receive ample practice opportunities for as they expanded their empire. The Romans were keen to suppress any idea that they were culturally influenced by the Etruscans, but religion is one area where they acknowledged their debt more readily. Soothsayers and diviners became a staple member of elite households, rulers' entourages, and even army units, and if that learned individual was an Etruscan or of Etruscan descent, the acknowledged experts in such matters in the Mediterranean, then so much the better.