Electra is a play written by the 5th-century BCE Greek tragedian Sophocles. Similar to Aeschylus' Libation Bearers, Electra focuses on the return of Electra's brother Orestes from exile and the plot to murder their mother. Years earlier, their mother Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus killed their father Agamemnon upon his return from the Trojan War. In this version of the story, Electra has been treated as a slave since the death of her father. She tries to procure the assistance of her sister Chrysothemus in her plot but fails. With the return of Orestes and his friend Plyades, Electra is able to successfully avenge her father's murder.

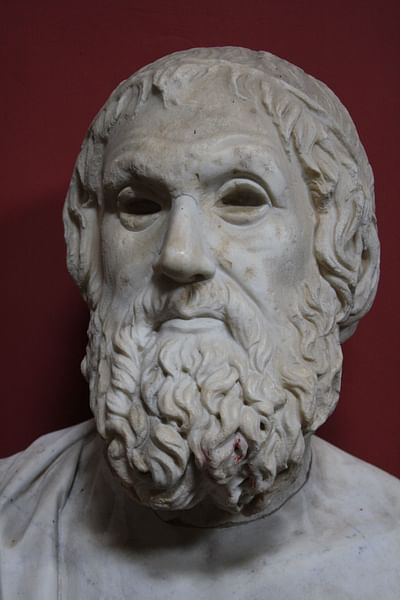

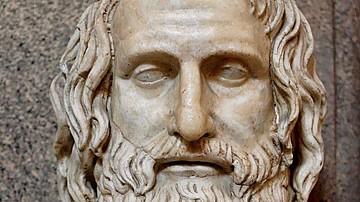

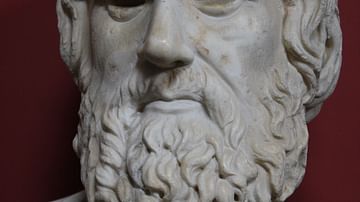

Sophocles

Sophocles (c. 496 BCE - c. 406 BCE) is considered one of the most successful tragedians of his time. He wrote at least 120 plays but, unfortunately, only seven have survived. Of his surviving plays, the most famous is Oedipus the King, part of a thematic trilogy along with Antigone and Oedipus at Colonus. He won 20 victories in play competitions; 18 of them were at the Dionysia. Writing almost until the day he died, his final play Oedipus at Colonus was presented by his son Iophon in 401 BCE.

Sophocles was born to a wealthy family in the suburb of Colonus outside the city of Athens and was extremely active in Athenian public life, serving as a city treasurer in 443-42 BCE and a general with the statesman Pericles 441- 40 BCE. When he was in his eighties, he was named a member of the group of special magistrates assigned to the dubious task of organizing both financial and domestic recovery in 412-11 BCE after the disastrous Athenian defeat at Syracuse on the island of Sicily. He had two sons by his wife and one by his mistress. Two of them would eventually become playwrights.

Although active in Athenian politics, his plays rarely contain any references to current events or issues. Classicist and author Edith Hamilton in her The Greek Way wrote that he was a passionless, detached observer of life. She believed the beauty of his plays was in their simple, lucid, and reasonable structure. He was the embodiment of what we know to be Greek. Moses Hadas in his Greek Drama said that Sophocles represented his characters as they should be while Euripides saw them as they were. Editor David Grene in his translation of Oedipus the King said that his plays had tightly controlled plots with complex dialogue, character contrasts, an interweaving of spoken and musical elements, and the fluidity of verbal expression.

Summary

The play begins with Orestes, son of Agamemnon and brother of Electra, returning to Mycenae and plotting his revenge against his mother. He tells his old slave to go to the palace and announce to Clytemnestra that Orestes is dead. He and Plyades will use the urn containing his supposed ashes to gain access to the palace. Meanwhile, Electra is pacing before the palace, bemoaning her plight in life and ranting against her mother and her lover, Aegisthus. The years have not quelled her intense hatred. Her sister, Chrysothemis, exits the palace and is confronted by Electra. Over the years, Chrysothemis has become complacent and somewhat accepting of her mother's role in her father's death. Later, when asked to join in a plot to kill their mother and Aegisthus, she will refuse.

When Clytemnestra and Electra meet outside the palace, they argue; Electra is even threatened with exile. The old slave arrives and speaks to Clytemnestra, telling her of her son's valiant death in a chariot race. Electra is heartbroken. When Chrysothemis returns from offering libations at their father's grave, she tells her sister that she believes Orestes is still alive and in Argos. Electra informs her of the news of Orestes death. Shortly, Orestes and his friend Plyades arrive with the urn, and, after convincing Electra of his identity, they enter the palace, killing Clytemnestra. Later, when Aegisthus returns, he, too, is killed.

Cast of Characters

- Old slave

- Orestes

- Electra

- Chorus of women of Mycenae

- Chrysothemis

- Clytemnestra

- Aegisthus

- Plyades

- Attendants

The Play

The play opens with Orestes, son of Agamemnon, his friend Pylades, and an old slave standing before the royal palace at Mycenae. The old slave recounts an old story to Orestes:

From here, some years ago, when your father was murdered, your sister Electra handed you into my care. I carried you off. I saved your life. (136)

He reminds him how it is now time to avenge his father's death. Orestes speaks of his time at the oracle of Apollo where he was told that the time had come to shed blood and a plan he has devised. In it, the slave will appear at the palace doors with news that Orestes is dead and his body has been cremated. He continues:

And now for us. First, we'll pour libations on my father's grave as the god instructed, and crown it with curling locks cut from my head, before we retrace our steps, bearing with us the urn of bronze. … Our crafty tale will bring them the glad tidings. (137)

After the three leave, Electra appears from inside the palace and bemoans her lot in life:

My hateful bed in a house of pain is witness to all my laments from my poor wretched father. (139)

She prays to the gods of the dead and the Furies to punish her father's murderers. She asks for them to send her brother home. Speaking to the chorus, she tells of her life - no children and no husband. She waits only for Orestes. Again she prays but this time to Zeus to avenge her father:

Those who committed such wickedness never should live to enjoy their splendor. (142)

Still speaking to the chorus, she confesses that her cries may make her appear embittered but admits that her mother is her bitter enemy. She hates seeing her mother's lover Aegisthus sitting on Agamemnon's throne, wearing his robes and sharing her mother's bed. The chorus chides her, claiming that her wretched state is her own making. However, she defends herself, asking how can she betray the departed. She adds that the delay of Orestes arriving has shattered her hopes. As she is standing there, her sister Chrysothemis appears and scolds Electra, saying that her anger is pointless. Unlike Electra, she chooses not to pose a threat; she does not have the strength necessary. Electra challenges her:

How can you forget the father whose child you are and only think of your mother? (146).

Chrysothemis tells her sister that their mother and Aegisthus plan to send her away, where she will never see the sun, but Electra is not frightened and says she plans to run away; she will not grovel. Noticing that her sister is holding libations, Electra asks where she is going. Chrysothemis says she has been sent by their mother to give libations at their father's grave. She relates a bad dream Clytemnestra had in which their father stood beside his wife and, taking hold of his staff, he planted it in the hearth where it grew into a tree that covered all of Mycenae. This frightened her. Electra asks her sister not to pour the libation and, instead, pray for the return of Orestes to avenge their father:

Do it to help me, do it to help the dear, dear father of us both, who lies in the house of Hades. (150)

Chrysothemis agrees. As she exits, Clytemnestra enters from inside the palace and confronts Electra. Speaking honestly, she admits that she killed Electra's father, however, "justice determined his death" (152). Agamemnon committed a barbaric crime, sacrificing their daughter Iphigenia to help the Greeks. Ignoring her mother's excuses, Electra says it was not justice that drew her to the bed of Aegisthus. Agamemnon sacrificed her sister "under compulsion" from Artemis, not for Menelaus and Helen.

Even if it were true, as you maintain, that he did it to help his brother, did that entitle you to murder him? (154)

She blames her mother for bullying her into a wretched life. Clytemnestra retorts:

I swear by Artemis you'll pay for his insolence as soon as Aegisthus comes home. (155)

As they stand there arguing, the old slave approaches them. Addressing both, he says he is the bearer of sad news; Orestes is dead. As she hears this, Electra's heart is broken; there is now no reason to live. Clytemnestra tells the slave to ignore Electra and asks how Orestes had died. Orestes had competed at a Panhellenic festival, the Pythian Games. Unfortunately, he was thrown during a chariot race. He was burned on a pyre and his ashes placed in an urn. She wonders whether this is good news or sad news. Electra exclaims that her mother is having a moment of triumph and asks the god Nemesis to avenge her brother. She mocks her mother's grief and calls her wretched.

As Clytemnestra and the old slave enter the palace, Electra recognizes that Orestes' death means he can never return home to avenge his father's death. As she bemoans her plight, Chrysothemis enters exclaiming; Orestes is back. At the family vault, she saw libations, garlands of flowers, and a lock of hair. It had to be Orestes. Electra calls her a fool and tells her of the old slave's claim that Orestes is dead. Their hopes are gone. Electra then asks her to join in a plan to kill Aegisthus. Chrysothemis asserts that neither of them has the strength necessary. Electra calls her a coward and says she will act alone.

Orestes and Plyades arrive at the palace. They ask the chorus leader to announce their arrival. They are looking for Aegisthus. Meeting Electra, they say they are holding an urn with the ashes of Orestes. Electra takes the urn and tells them it is "All that's left to remind of the life that I loved best in the world, home to me now" (175). She covets death now. She speaks of her life and tells him of her father's murderer; her mother. Orestes conveys his pity for her. She explains how she had hope, but now he has brought the ashes of her only hope; her brother. Orestes finally confesses that the urn does not contain Orestes and reveals his identity but asks her to keep it a secret.

No need to explain how vile our mother is, or how Aegisthus is draining our father's wealth by extravagance and waste. (180)

The old slave greets them at the palace door and chides them, asking them to be cautious and “stop this endless talking and these cries of insatiable joy” (181). The old slave takes them into the palace. Later, Electra exits and speaks to the chorus leader, she is waiting for Aegisthus. Soon, they hear the cries of Clytemnestra from inside the palace, begging Orestes to have mercy. Orestes exits from the palace with a hand "dripping red." Speaking to Electra, Orestes says:

Your mother's spike shall never hurt you again. (186)

Aegisthus appears and asks if the men have arrived from Phocis with news of Orestes. Electra informs him that they are in the palace with her mother. As they speak Orestes and Plyades exit the palace carrying Clytemnestra's body. As they draw their swords, Aegisthus realizes that it is Orestes. They take him into the palace while the chorus leader speaks to Electra; she has her freedom.

Conclusion

Undoubtedly, the trilogy Oresteia written by another great Greek tragedian Aeschylus influenced Sophocles in the retelling of the story of Electra and her life-long desire to kill her father's murderers: her mother Clytemnestra and her mother's lover Aegisthus. In the second play of the trilogy, Libation Bearers, Orestes returns home after a long exile. He meets Electra at their father's tomb and formulates a plot to kill their mother and Aegisthus. In Aeschylus' interpretation, Orestes and Plyades appear at the palace posing as travelers with the sad news of Orestes' death. After entering the palace they kill both Clytemnestra and her lover.

Sophocles' tale is slightly different. An old slave brings news of Orestes' death. Later, Orestes and Plyades arrive with an urn, supposedly carrying the ashes of Orestes. After revealing his identity to Electra, he enters the palace and kills their mother. When Aegisthus arrives, he, too, is killed. Both murders are committed inside the palace, out of the chorus' view. Some interpret the play to be more about revenge than matricide; the latter being the focus of Libation Bearers. In Sophocles play, Electra and her sister are opposites; Electra is tormented by her bitter hatred while her sister has become far more complacent, refusing to participate in a revenge plot. In the end, both brother and sister are set free. Unlike with Aeschylus, there is no second play to reveal their destiny.