Modern practitioners of Judaism and Christianity often turn to the Bible for stories concerning women and their roles in ancient religion and society. It is important to acknowledge that these stories were written by men. The male perspectives provide little information about the actual thoughts and feelings of women.

Many of these stories include ancient prejudices against women. However, there is a broad range of both positive and negative views. Each story has a historical as well as a literary context that influences interpretation. For the most part, the stories of women are juxtaposed to critique the behavior of men in some surprising ways.

The Social Construction of Gender

One’s physical sex is defined by the biological differences at birth. One’s gender is a social construction, determined by codes of behavior. All ancient societies had these law codes, claiming that they were established by the gods. The dominant theme in the construction of gender was fertility; without fertility of herds, crops, and especially people, the group would not survive. Divine powers were thus portrayed in pairs, with each god having a female goddess as consort. Mirroring the heavens, the basic social unit of the ancient world was the family. Each family member had religious and social duties that contributed to survival.

Historians describe ancient cultures as patriarchal or matriarchal. Patriarchy is a system of male rulers and descendants are traced through male progeny. A matriarchy posits a system measured through the mother’s bloodline. However, these are not defined categories, as there was overlap between the systems. For example, men also worshipped fertility goddesses.

Women as Property

The easiest way to think of the social roles of women and men in the Jewish Scriptures is through analogies of property or contract laws. A woman at birth was the property of her father who then completed a marriage contract for her. She was handed over to her husband, with details of goods transferred in a dowry. There were also betrothal contracts. Puberty was recognized as the time when boys and girls were ready to move into the adult world and bear children. Women married at the ages of 12-16, while boys used their teenage years for military training. The age for marriage for boys varied from culture to culture, anywhere from 18 to 30. The age difference meant that there are numerous stories of widows in the Bible.

Then as now, some marriages went wrong. In that case, another contract was required to undo the original; a contract of divorce. Among the reasons for divorce were infertility and the renegotiation of marriage partners with changing political dynasties. Most ancient cultures had harsh punishments for adultery. Adultery meant the violation of another man’s property. In an age of no DNA tests, paternity had to be assured to maintain the correct bloodlines. This led to the sheltering and protection of women against other males. Veiling was required when women went out in public as a deterrent against the straying eyes of other men.

For the most part, the Jewish Scriptures incorporated the dominant gender roles of ancient society, including the details of marriage and divorce in the Law of Moses. Among the founders of the nation of Israel, we have named matriarchs as well as patriarchs. They are often set in pairs: Adam and Eve, Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, Jacob and (his two wives) Leah and Rachel. The first commandment of God in Genesis was "Be fruitful and multiply" (Genesis 1:22).

Typology of Biblical Women

Typology refers to classifications, either of people or events, that often serve as tropes, or figurative or metaphorical use of a word or expression. A popular type was that of the barren woman. Many of the biblical women have this problem either through age (Sarah) or infertility (Rachel). Barrenness was not a sin. All these stories are followed by the device of anti-type, a reversal of stereotypical expectations. The reversal begins with an annunciation story where either God or an angel reveals that the woman will become pregnant through divine intervention. The announcement follows a pattern: a son will be born (it is always a son), whom God will raise up above the people, to help fulfill the divine promises of God. Narrative writing also employs conflicts and resolutions, held together by plot tension. When God promises Abraham that he will be the father of a great nation - "I will make you into a great nation" (Genesis 12:2) - Abraham is old and Sarah is barren. Achieving this promise drives most of the plot in the first half of Genesis.

In the case of an older or infertile wife, Jewish law in this period allowed the taking of a second wife. Older translations often use the term "concubine", but these were legally contracted second marriages. This was the ancient equivalent of our modern surrogate mother. By law, the offspring from this union belonged to the father and his first wife. Sarah told Abraham to "go, sleep with my slave", Hagar (Genesis 16:2). This was not adultery; slaves were the property of their masters. Hagar got pregnant with their son, Ishmael. However, God reminded them that this was not the son of the promise, but Ishmael would also be the father of a great nation, the Arabs.

When God called Abraham and told him to move to the land of Canaan, he was told not to mix with the local population because the locals were idolaters. There was an ancient conviction that women would utilize their sex to control men and so local women might lead Abraham’s people into idolatry. After the birth of Isaac, Abraham sent a servant to the town of Haran (northern Iraq) where he had some relatives to find him a wife. Starting with Abraham’s servant, the next several women in Genesis and beyond are found at the town well. The well (water) was a symbol of life, and this is where the annunciation stories often took place. Abraham’s servant met Rebecca at a well, Jacob met Rachel at a well, and Moses found his wife, Zipporah, at a well.

Rebecca is not barren, but two sons struggled in her womb, Jacob and Esau. This is another typological device, that of the younger son who usurps the elder. Many ancient cultures followed primogeniture, or the elder son inheriting his father’s estate. At birth, Jacob was grabbing the heel of his brother, attempting to be born first. Esau was the eldest, but Rebecca helped Jacob to steal the birthright of his brother. Rebecca is honored with having the insight to assure that the promised line of descendants goes through Jacob. After Jacob’s trick, he had to flee from his brother’s wrath to Haran. Seeing Rachel at the well, he asked her father for her hand. Laban agreed but only after Jacob worked for him for seven years. At the wedding, he discovered that her older sister, Leah was given instead. Laban told Jacob he could have both, after laboring another seven years.

Genesis then related what became the official begets, or the bloodlines of this family. Both Rachel and Leah go through periods of barrenness when they offer their servant women to Jacob. Rachel’s story is a poignant one. When she cried to Jacob "Give me children, or I’ll die!" (Genesis 30:1), it reflects that a woman’s identity was tied to her ability to bear children. "I will die" meant that without issue, she would not be remembered in Israel. Early ideas of an afterlife were based upon one’s name surviving. In stories of women who are not named, it is usually because they did not have a child.

Four women produce the sons who became the twelve tribes of Israel. The text goes into detail, as a reflection of the later distribution of tribal territory in Canaan. It is coordinated depending upon the identity of their mothers, Leah and Rachel, or the two servants.

Righteous Prostitutes & the Canaanites

Surprisingly, the Scriptures relate several stories of women of the anti-type, or women who do not fit the stereotype. Prostitution was not a sin; without marriage contracts, there was no violation of another man’s property. However, they were at the bottom of the social scale because the ancients did not know that semen regenerates. A man should not be wasting his seed on a prostitute, but rather fathering children in his bloodline.

In the book of Joshua, Israelite spies were sent into Jericho to determine the city’s defenses. They went first to a brothel, where the madam, Rahab, a Canaanite, agreed to hide them. She did this because she believed in the God of Israel, who would be victorious. Such stories are polemical admonishments against Israelite men; they are used as examples when the men falter in their loyalty to God.

In the book of Judges, we learn of Deborah, a prophetess as well as a judge of Israel. We find the same reversal of stereotypes in her story. The Israelite general, Barak, was hesitant to lead a battle without Deborah riding in his chariot. Deborah did so, but denounced Barak for his lack of faith in God: "the honor will not be yours, for the Lord will deliver Sisera into the hands of a woman" (Judges 4:9). Yael (in later texts, Judith) a local camp follower killed the Canaanite general. Drawing him into her tent, she pounded a tent peg into his head after he fell asleep.

The elevation of some women in leadership roles emphasized the failures of male leadership. Queen Esther won a beauty contest to become the wife of the Persian king Ahasuerus (a fictionalized Xerxes I). She foiled the plan of Haman, the king’s counselor, and stopped the persecution of the Jews (the later holiday of Purim).

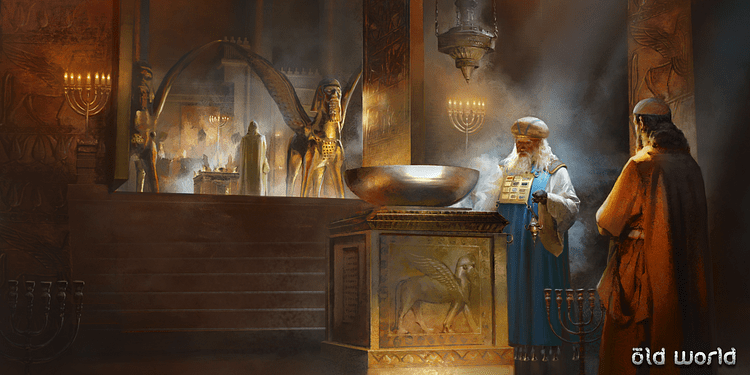

The Impurity of Women

Modern views of the lives of ancient Jewish women are often negatively denounced as oppressive to women because of the purity codes in the book of Leviticus. All ancient societies had purity rituals. Purity was not necessarily related to hygiene but was a state of being. The concept separated sacred things from mundane (everyday life) things. Approaching the altar, one had to be in a state of ritual purity so as not to violate the sacred space. The two sources of life, blood and semen belonged to God and so any involvement of those fluids had to be set aside, where daily routines were suspended. Intercourse was not a sin, but a man was unclean for a day and a night. Women’s menstrual cycles and childbirth involved blood, so the necessary separation had to take place for a certain number of days (Leviticus 12).

Two stories of women have become infamous and are applied as metaphors in our culture: Jezebel and Delilah. The book of Judges relates the story of Samson and his battles against the Philistines. Samson, the son of another elderly and barren couple, was to be a Nazarite from birth in answer to their prayers. Nazarite vows were taken as a way in which to shun normal activities and dedicate one’s life to God. This included not cutting one’s hair, a social convention. Other than his long hair, Samson rarely held to these vows.

Judges 16 related the story of Delilah, a Philistine woman who had become Samson’s latest love interest. The Philistines ordered her to discover the source of Samson’s strength. After three attempts (wheedling it out of him), he revealed that the source of his strength was in his hair. After he fell asleep, Delilah cut off his hair, enabling the Philistine to capture him. Modern images of Delilah associate her with seduction, as a stereotypical temptress. However, there is nothing in this story that suggests that she was a loose woman. Her condemnation resulted from who she is, an idolater, and working for Israel’s greatest enemy, the Philistines.

The story of Jezebel (a Phoenician princess) is found in 1 Kings 16. She was the wife of one of the evil kings of Israel, Ahab. Jezebel was a follower of Ba’al and Astarte, Canaanite fertility deities. She violently opposed the Prophets of Israel and banished them, and convinced Ahab to go along with setting up altars to these gods. The Prophet Elijah challenged her in a battle of the Prophets to determine whose god was the most powerful. Elijah won.

After Ahab’s death, learning that (the next king) Jehu was on his way, she dressed up with a wig and jewelry to taunt him. Jehu ordered her servants to toss her out of her window. Her body was eaten by dogs, fulfilling a prophecy. Again, although "Jezebel" has come to be synonymous with "seductress", her downfall had nothing to do with her sex. She is condemned for her persecution against the Prophets and her idolatry.

The Prophets of Israel served as oracles, or ways in which God communicated with humans. Like the other stories in the Scriptures, women are used as models of either ideal or negative behavior. In the Prophets’ condemnation of idolatry, they applied sexual metaphors to this sin of Israel. Both the prophets Elijah and Elisha performed miracles and spent time with Canaanite widows to demonstrate that their faith was greater than the Israelite men. Because of so many sexual metaphors, the wiles of women became embedded in the Western tradition and were later applied by Christian leaders in their treatises on women.

Other Notable Women in the Jewish Scriptures

Eve

The creation of the first woman in Genesis designated Eve as "the mother of all living" (Genesis 3:20) and is at the center of the fall story in Eden. She convinced Adam to eat the forbidden fruit, and thus mortality entered the lives of humans. Both later Rabbinic texts as well as Christian teaching claimed that she seduced Adam. Augustine of Hippo (5th century CE) made this the focus of the innovative Christian doctrine of the original sin. This seduction by Eve still resonates in Western literature, art, and views of the nature of women.

The book of Ruth takes place in the time of Judges. It tells the story of Naomi who left her homeland in Bethlehem and married a man in Moab (a tribe that was an enemy of Israel). She had two sons who married local women. When her sons died, and she was widowed, she wanted to return to Bethlehem. Naomi told her daughters-in-law that they should remain.

Ruth spoke up:

Where you go I will go, and where you stay I will stay. Your people will be my people and your God my God. Where you die I will die, and there I will be buried. May the Lord deal with me, be it ever so severely, if even death separates you and me. (Ruth 1:16-17)

Many people continue to utilize this passage in wedding vows.

As widows, gleaning in the fields of the local landowner in Bethlehem, Naomi advised Ruth to meet with the owner, Boaz, that night at the threshing floor. Ruth was to uncover his feet, a euphemism for sexual intercourse. Boaz took both women under his care. Ruth became the grandmother of King David. The main purpose of the book is twofold: an explanation of the concept of hesed ("loyalty") and a demonstration that intermarriage with non-Jews does not always lead to corruption.

Bathsheba

In Samuel 1, King David noticed a woman bathing on her roof and had her brought to him. Bathsheba was married to Uriah the Hittite, who was away fighting David’s battles against the Philistines. After she became pregnant, David attempted to hide the adultery by recalling Uriah for a battle report and then told him to go home and see his wife. Uriah did not think he deserved this while the other men were fighting, so he refused to leave the court. David ultimately sent him back to the frontlines, with a note that the commander should put him in line for some friendly fire.

Having committed both adultery and murder, the baby is stillborn. In their grief, Nathan the Prophet told them not to worry; God will establish a line of David’s descendants who "will never fail to have a successor on the throne of Israel" (1 Kings 2:4). The plot tension here is that as soon as this covenant (contract) with David is pronounced, King David’s sons plot against him to overthrow the throne. Bathsheba became pregnant again with their son Solomon. She then maneuvered to have Solomon inherit the throne.

The Judgment of Solomon

I Kings 3:16-28 tells the story of two women who brought a case before the king. The women are not named but are designated as prostitutes. As such, there is no legally contracted male partner to speak for them. Both women had recently given birth, but during the night, one of the babies had been smothered and died. Each claimed to be the mother of the surviving child. Solomon issued his judgment: "Cut the living child in two and give half to one and half to the other" (I Kings 3:24). One woman agreed while the other protested in horror, claiming that she would rather give the baby up than to see it die. Solomon ruled in her favor. This unnamed woman became a model for 'true motherhood' while the 'judgment of Solomon' has also become a modern metaphor for enlightened strategy in judicial rulings.