The Clouds is a comedy written c. 423 BCE by the Greek playwright Aristophanes (c. 448 BCE – c. 385 BCE). A failure at the Dionysia competition, finishing third out of three, it was revised later in 418 BCE but never produced in the author's lifetime. The play as it now appears is believed to be the revised version. In The Clouds a familiar theme reappears. As in another Aristophanes play, The Wasps, a troubled traditional father is pitted against his citified young son; the old versus the new. Strepsiades, the father, is an old farmer who had married well beyond his means and whose son, Pheidippides, has an affinity for horses. Unfortunately, the son has accumulated a large debt which the father cannot repay. In an attempt to avoid facing his creditors, the old man goes to a nearby school run by Socrates - The Thinkery - to learn how to argue, making a wrong argument right. Although the father fails miserably as a student, he is able to convince his son to attend the school. In the end, the young Pheidippides learns well enough to even defend the beating of his own father.

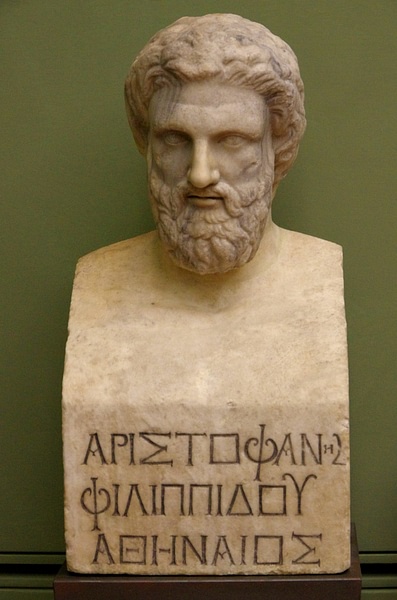

Aristophanes

Little is known of Aristophanes' early life; even his birth date is questioned. He was born in the Cydethanaeum district of Athens to Philippus and Zenidora. His family may have owned property on the island of Aegina, which caused his critics to claim he was not a true Athenian. His lone political endeavor was serving on the Council of Five Hundred. He had two sons, Aroses and Philippus, both of whom became comic dramatists. Aristophanes initiation into the world of drama came while serving an internship in the 420's BCE, aiding other dramatists with scripts and production. The traditional Greek theater as it had existed under the tragedians Sophocles and Aeschylus was in decline, soon to be replaced by comedies. Unfortunately, Aristophanes is the only representative of Old Attic Comedy whose plays - 11 of more than 40 - have survived.

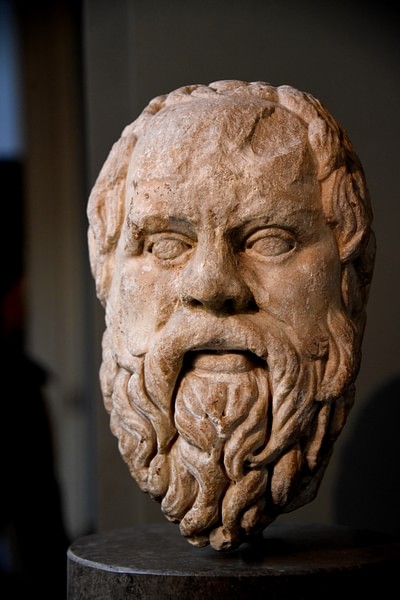

Although drama had changed, some things away from the theater had not. The war against Sparta was still waging, and Aristophanes' personal character and animosity towards the Athenian government became apparent throughout his plays. His conservative nature voiced that of many loyal Athenians who still valued the old simplicity and morality of the past, viewing all new innovations as being rebellious. Aristophanes' favorite targets were politicians, poets, and especially philosophers. His attacks on various Athenian politicians such in the plays The Babylonians and The Knights brought him into court twice. In The Clouds, he chose the premier Greek philosopher Socrates as his object of ridicule.

Characters

There are relatively few major characters in the play:

- Strepsiades

- Pheidippides

- Socrates

- a slave

- a student

- Right

- Wrong

- first creditor

- second creditor

- Chaerephon

- the chorus of cloud goddesses

- and the silent characters of Xanthias, a witness, and several more students.

plot

The play begins in a courtyard where an old farmer Strepsiades attempts to sleep. His young son Pheidippides sleeps nearby under a pile of blankets. The cranky old father speaks out loud, initially against the consequences of the war with Sparta but soon turns his attention to his lazy son. The father laments about his son's fascination with horses and horse racing; something that has brought both bills and massive debt:

I'm being bitten all over, Not by bugs - by horses and bills and debts, on account of this son of mine, him and his long hair and his riding and his chariot and the pair. (Sommerstein, 75)

In frustration he finally wakes Pheidippides. The father reveals to his son that he has judgments against him; his creditors are threatening to seize his goods. Hoping to convince his son of the seriousness of this, he adds that one day these huge debts will be his. Strepsiades begs him to change his ways by taking a course of study at the nearby Thinkery, a school for intellectual souls. However, the son is reluctant.

I know the villains. You mean those pale-faced bare-footed quacks such as that wretched Socrates and Chaerephon. (78)

The son wants to know why he should go; what is he is to learn there. The father tells him that the Thinkery teaches two forms of arguments, Right and Wrong. If he can learn how to argue - mostly from Wrong - then he will be able to help get his father out of debt. “They can teach you how to win a case whether you're in the right or not.” (78) Unfortunately for Strepsiades, the son refuses; he would never be able to face his friends again with the color drained from his face. So, instead of trying to persuade his son otherwise, he decides to go to the Thinkery himself and learn how to argue.

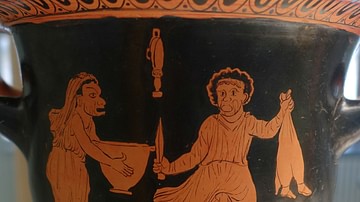

After knocking on the school's door, he is greeted by one of Socrates' students. Although annoyed, the student speaks of the great philosopher's intellect, citing a recent discussion of a flea's feet with Chaerephon. After entering the school, Strepsiades is informed of some of the amazing things going on there; he is shown several mathematical and scientific instruments, even a large map of Athens. Finally, he is introduced to Socrates who is seen hanging from the ceiling. He tells the father that he is studying the mystery of the sun. When the old man swears by the gods that he will pay whatever Socrates charges, the philosopher immediately turns the discussion to religion, the plain truth of religion and the importance of the Clouds. Socrates sings: “Come, glorious Clouds, display your powers” (85). Suddenly the celestial Clouds appear, and Socrates explains:

From them we get our intelligence, our dialectic, our reason, our fantasy and all our argumentative talents. ... They give sustenance to a vast tribe of sophists, high-powered prophets, teachers of medicine, long-haired idlers with fancy signet rings, and especially the airy quacks who write those convoluted dithyrambs. (85-88)

Socrates tells the skeptical Strepsiades that they are the real divinities; there is no Zeus. The confused old man promises to never make a sacrifice to a god again and claims he is ready to learn to be the best orator in Greece. In order to test his intelligence, Strepsiades is asked a number of questions. Does he have a good memory? Is he a natural speaker? No! He is, however, a natural swindler. Socrates is confused and takes the old man's cloak; no one wears a cloak inside the school. Socrates and the old father exit briefly into another room, leaving the Leader of the Clouds to speak to the audience. Upon returning, Socrates exclaims:

In the name of Respiration and Chaos and Air and all that's holy, I've never met such a clueless stupid forgetful bumpkin in all my life. The most trifling little thing I teach him, he forgets before he's even learnt it! (98)

He becomes more and more frustrated. He tries to explain the differences between the names of objects - masculine and feminine - but he soon realizes it is hopeless. Desperate, Strepsiades turns to the Leader of the Clouds for advice and is told to send his son. After a long talk, including his own experiences at the Thinkery, the father convinces his son to go to the school. Reluctantly, Pheidippides follows his father to the school, but Socrates is not impressed. He finally submits and says he will accept the boy into the school. Luckily, he is to be taught by the Arguments themselves; Socrates will not be there.

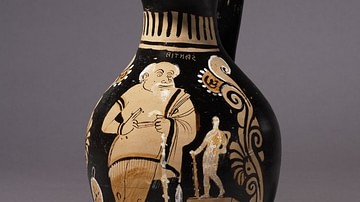

Right (depicted as an old distinguished-looking man) intends to make a case for justice. To counter this statement Wrong contends that there is no such thing. Right says that justice is to found with the gods. If this is true, Wrong (portrayed as a young unhealthy man) asks, then why was Zeus not punished for putting his father in chains. Right calls Wrong a young pansy after he is called an old windbag. Right challenges Wrong's character:

You're the one that encourages our adolescents to drop out of school. One day Athens will wake up to what you've been doing to these young people who don't know any better. (109)

Right adds that he hopes to be Pheidippides' teacher so the young man can lead a decent life "and know how to do something besides talking" (109). Both are finally asked by the Cloud Leader to explain their method of teaching; old versus new education. Right says that in his day children were seen and not heard; discipline was important and one did not interrupt the father. The anxious Wrong turns to the Pheidippides and tells him the virtuous cannot do a lot of things, a lot of pleasures are to be lost: no gambling, no women, and no fancy food. Is life worth living? Right finally gives in. Wrong wins.

Later, it is the end of the month and the creditors want their money. After retrieving his son from the Thinkery, the father is standing outside his own home. The old man hopes that his or son's ability to argue will help avoid his debts. Soon, the first creditor arrives asking for payment, but Strepsiades confuses him with his jumbled logic. The confused creditor leaves but is soon followed by a second one. The old father charges that the creditor is “suffering from some form of concussion of the brain" (121). After a serious of nonsense questions, the second creditor also leaves.

The father enters the house only to exit quickly, claiming that his son has beaten him and demands to know why. Pheidippides replies that he can justify his actions. The chorus questions how the altercation began. Strepsiades says he asked his son to recite Aeschylus, the prince of the poets, however, the son instead recited Euripides. The father calls his son a name, so the son hit him. The son explains:

I'm intimate with all the newest and subtlest ideas, principles, and I'm confident I can demonstrate that it is right and proper to chastise one's father. (126)

Pheidippides asks his father if he had beaten him as a child. The father says he did it because he cared, and so the son concludes that beating equals caring and adds that is even proper to beat one's mother. For that, he should be thrown off of the Acropolis. After the son denies the existence of Zeus, the old father prays to Hermes to have pity. Frustrated, he asks his slave Xanthias for a torch. They climb to the roof of the Thinkery and set it on fire. Socrates and his students escape but are pursued by Strepsiades and his slaves.

Interpretation & Legacy

Aristophanes' comedies were seen as a masterful blend of wit and invention. Often criticized for their crude humor and suggestive tone, his plays were popular among the Athenian audiences. However, to his many critics, he brought Greek tragedy down from the high levels of such tragedians as Aeschylus with his use of parody, satire, and vulgarity.

In his play The Clouds, Aristophanes revisits an old theme; the old or traditional versus the new or innovative. The conservative anti-war author wrote against a changing Athens and chose the philosopher Socrates as a symbol of this change. To him, Socrates represented all that he disliked about a new Athens. The traditionalist author treasured the simplicity and morality of a bygone era. In reality, Socrates spoke to the youth of the city, having them challenge and question both old customs and the government. Of course, this challenge is what brought him to trial and his eventual death. In the play, at the Thinkery, a fictionalized school run by the esteemed philosopher, Right represents the old discipline, morality, and respect while Wrong voices the aims of the new education, to enjoy life. In the end, the son has learned his lessons well and even rationalizes hitting his father.

Although the play was unsuccessful in competition, it did survive, unlike those of his contemporaries. While it makes the mistake of identifying Socrates as a sophist, it was successful in its attempt to demonstrate a city in transition.