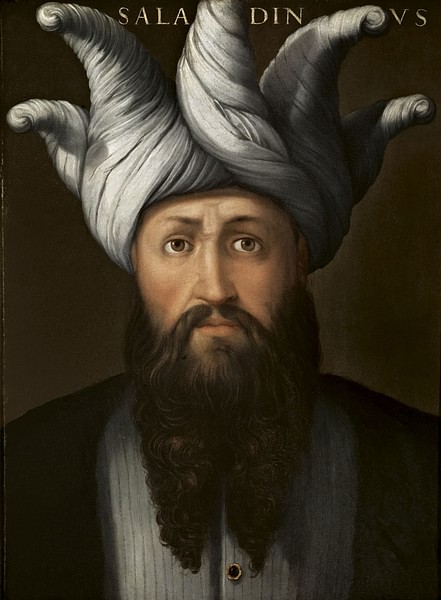

Saladin (1137-93) was the Muslim Sultan of Egypt and Syria (r. 1174-1193) who shocked the western world by defeating an army of the Christian Crusader states at the Battle of Hattin and then capturing Jerusalem in 1187. Saladin all but destroyed the states of the Latin East in the Levant and successfully repelled the Third Crusade (1187-1192).

Saladin achieved his success by unifying the Muslim Near East from Egypt to Arabia through a potent mix of warfare, diplomacy and the promise of holy war. Saladin's skills in warfare and politics, as well as his personal qualities of generosity and chivalry, resulted in him being eulogised by both Christian and Muslim writers so that he has become one of the most famous figures of the Middle Ages and the subject of countless literary works ever since his death in his favourite gardens of Damascus in 1193.

Early Career

Saladin, whose full name was al-Malik al-Nasir Salah al-Dunya wa'l-Din Abu'l Muzaffar Yusuf Ibn Ayyub Ibn Shadi al-Kurdi, the son of Ayub, a displaced Kurdish mercenary, was born in 1137 in the castle of Takrit north of Baghdad. Saladin would rise through the ranks of the military where he gained a reputation as a skilled horseman and a gifted polo player. He followed his uncle Shirkuh on campaign, who conquered Egypt in 1169. Saladin then took over from his relative as the governor of Egypt for Nur ad-Din (sometimes also given as Nur al-Din), independent governor of Aleppo and Edessa (r. 1146-1174). The historian J. Phillips gives the following succinct description of the young Saladin:

…a short man, with a roundish face, a trim black beard and keen, alert black eyes. He placed members of his family in positions of power and seemed to challenge his master's authority. (262)

When Nur ad-Din died in May 1174 his coalition of Muslim states broke up as his successors battled for supremacy. Saladin claimed that he was the true heir and took Egypt for himself.

Unifying the Muslim World

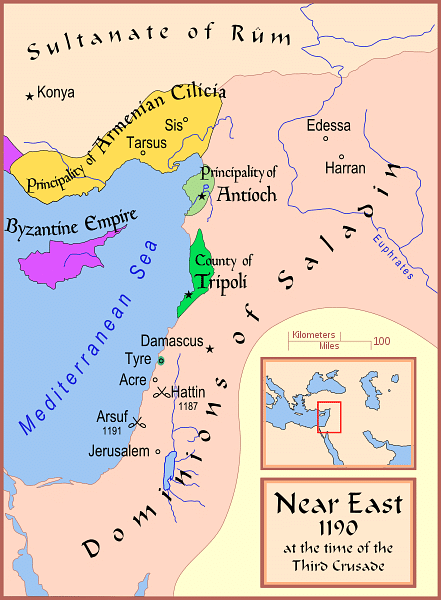

Saladin, now the Sultan of Egypt, repeated the feat of Nur ad-Din in Syria when he captured Damascus in 1174. Saladin claimed to be the protector of Sunni Orthodoxy and his removal of the Shiite caliph in Cairo and organisation of his state according to strict Islamic law gave this claim serious weight. Saladin then set about unifying the Muslim world or at least forming some form of a useful coalition - no easy task given the many states, independent city rulers and differences in religious beliefs of the Sunni and Shiite Muslims.

Saladin's strategy was a potent mixture of warfare and diplomacy mixed with the idea that he and only he could wage a holy war against the Christian settlers in the Middle East who had formed such Latin states as the Kingdom of Jerusalem. First, though, the military leader had no qualms either about waging war on his Muslim enemies. In 1175, for example, an army from a rival at Aleppo was defeated by him at Hama. Saladin's supremacy amongst the Muslim leaders was cemented when the caliph of Baghdad, the head of the Sunni faith, formally recognised him as the governor of Egypt, Syria and Yemen. Unfortunately, Aleppo remained independent and, ruled by the son of Nur ad-Din, a serious thorn in Saladin's diplomatic side. There were more personal risks, too, as twice the Sultan of Egypt survived attempts on his life by the Assassins, a powerful Shiite sect. Saladin responded immediately by attacking the Assassin-held castle at Masyaf in Syria and pillaging the surrounding area.

Meanwhile, the diplomatic route was also pursued, chiefly in marrying Nur ad-Din's widow, Ismat, also the daughter of the late Damascan ruler Unur. Thus, Saladin handily associated himself with two ruling dynasties at one stroke. Along the way there were setbacks such as the defeat to the Franks, as the western settlers were known, notably at Mont Gisard in 1177, but victories in 1179 at Marj Ayyun and the capture of a large fortress on the River Jordan illustrated Saladin's intent to rid the Middle East completely of the westerners.

Also helpful to Saladin was his growing reputation for justice and generosity, and Saladin's own carefully cultivated image as the defender of Islam against rival faiths, especially Christianity. Saladin's position was further strengthened in May 1183 when he captured Aleppo and by his prudent build-up of a very useful Egyptian naval fleet. By 1185 Saladin controlled Mosul and a treaty was signed with the Byzantine Empire against their mutual enemy the Seljuks. He could now move on the Latin states safe in the knowledge that his own borders were secure. With the Franks distracted over conflicts of succession and the issue of who ruled the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the time for Saladin to strike was now.

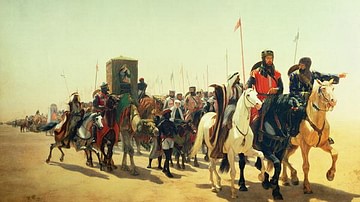

In April 1187 the Franks' castle of Kerak was attacked, a force commanded by Saladin's son, al-Afdal, moved towards Acre and Saladin himself gathered together a huge army composed of troops from Egypt, Syria, Aleppo and Jazira (northern Iraq). The Franks gathered their forces in response and the two armies met at Hattin, the Franks on their way to Tiberias to relieve Saladin's siege there.

Battle of Hattin & Jerusalem

The battle of Hattin began on 3 July 1187 when Saladin's mounted archers continuously attacked and retreated, providing a continuous harassment of the marching Franks. As one Muslim historian put it: 'the arrows plunged into them transforming their lions into hedgehogs' (quoted in Phillips, 162). The next day, a more substantial engagement ensued. Saladin was able to field some 20,000 troops at Hattin. The Franks were under the leadership of Guy of Lusignan, king of the Kingdom of Jerusalem (r. 1186-1192) and could field around 15,000 infantry and 1,300 knights. The Franks were outnumbered and seriously short of water, while the Muslim army, with plentiful supplies thanks to their camel trains, set fire to the dry grass and brush to peak the enemy's thirst even further. The Franks' formation broke up with the infantry in disarray and no longer providing the usual protective ring for the heavy cavalry. A cavalry force led by Raymond of Tripoli did break through the Muslim lines but for the remainder of the army there was to be no escape and Saladin won a resounding victory against the largest army the Franks had ever assembled.

In a typical magnanimous gesture, Saladin offered the now captive Guy an iced sherbert. Some nobles were freed on the production of a ransom, as was typical of medieval warfare, including Guy. Others were less fortunate. Reynald of Chatillon, the Prince of Antioch, was hated for his earlier attack on a Muslim caravan and so was executed, Saladin himself first taking a swing with his scimitar and chopping off one of Reynald's arms. The knights of the two military orders, the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller, were considered too fanatical and too dangerous (besides offering zero chance of gaining any ransom) and so were executed too. The rest of the captives were sold into slavery.

In September 1187, Jerusalem, now almost totally undefended and a hugely symbolic prize for both sides, was captured by Saladin. Once again, a mass slaughter of the city's Christians was resisted and most were either ransomed or made slaves. Eastern Christians were permitted to remain in the city, although all of the churches except the Holy Sepulchre were converted into mosques.

Other important cities had already fallen under Saladin's rule and these included Acre, Tiberias, Caesarea, Nazareth, and Jaffa. Indeed, the only significant city still in western hands in the Middle East was Tyre. With the victory at Hattin, the capture of the Franks' holiest relic, the True Cross, and the fall of the Holy City of Jerusalem, Saladin's heroic status was confirmed. The Sultan was active in spreading his reputation, even employing two official biographers to record his deeds. So, too, religious and educational institutions were supported and their works extolled the virtues of their patron. The Sultan was known for his love of poetry, hunting and gardens. His generosity, in particular to his kinsmen who governed the provinces of his empire, was famed, too. This largesse and his lack of interest in accumulating personal wealth, is here recorded by the modern historian A. Maalouf:

His treasurers, Baha al-Din [Saladin's personal secretary and biographer] reveals, always kept a certain sum hidden away for emergencies, for they knew that if the master learned of the existence of this reserve, he would spend it immediately. In spite of this precaution, when the sultan died the state treasury contained no more than an ingot of Tyre gold and forty-seven dirhams of silver. When some of hi collaborators chided him for his profligacy, Saladin answered with a nonchalant smile: 'There are people for whom money is no more important than sand'. (179)

The Third Crusade

Saladin had long cultivated the idea of a holy war against the Christian armies of the west and he would have to wage it now that he had captured Jerusalem. Pope Gregory III (r. 1187) called for a Third Crusade to recapture Jerusalem and Europe's three most powerful kings responded: Frederick I Barbarossa, King of Germany and Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1152-1190), Philip II of France (r. 1180-1223) and Richard I 'the Lionhearted' of England (r. 1189-1199).

Meanwhile, Guy of Lusignan was back on the campaign trail. He had left Tyre with some 7,000 infantry, 400 knights and a small Pisan fleet to begin a siege of Muslim-held Acre in August 1189. It was the beginning of a long and arduous siege and with Saladin's land army besieging the Franks' positions, only the eventual arrival of Philip and Richard's armies swung the balance in favour of the Crusaders. The city was finally captured on 12 July 1191 and with it, significantly, 70 ships, the bulk of Saladin's navy.

The Crusader army then marched southwards towards Jerusalem with Saladin's army harassing them as they moved along the coast. Then a full-scale battle broke out on the plain of Arsuf on 7 September 1191. The Crusaders won the day but the Muslim losses were not substantial - Saladin having had no choice but to withdraw to the relative safety of the forest which bordered the plain. Although neither Acre or Arsuf had done any serious damage to Saladin's army, the two defeats in quick succession, and then the loss of Jaffa to Richard I in August 1192, did cumulatively damage Saladin's military reputation amongst his contemporaries.

Criticism of Saladin's Strategy

Saladin was frequently criticised by rival Muslim leaders for being too cautious when direct attacks on Tyre would have denied the Crusaders a crucial beach-head, and similarly, for not engaging Guy's army before he even reached Acre or the Crusader army on its arrival at the siege. All of these moves might have proved decisive. This was, though, to criticise with the benefit of hindsight and it ignores what were the commonly established rules of warfare of the period in the whole region. Armies of any kind very rarely directly engaged the enemy in open battle. Rather, the control of strategically important castles and ports through siege warfare was the standard practice of the day. The lack of determination to take Tyre, the last Frankish stronghold, is more difficult to defend, except that Saladin may have been wary of the arrival of Frederick I's huge army (which, in the event, never arrived) and preferred to keep faith with his tried and tested method of wearing down the enemy at their weakest points, not their strongest. He also knew that the western kings could not remain in the East indefinitely and so neglect their own kingdoms; time was always on the Muslim's side. And, as it turned out, Saladin's approach was successful, as the Crusader army, by the time it got to its primary objective of Jerusalem, was too depleted and Saladin's army was still such a threat, that the whole Crusade was abandoned in the autumn of 1192. A negotiated peace followed but Richard I gained very little for all the effort put into the cause, not even managing to meet his opposite number face to face. Saladin, meanwhile, still had Jerusalem, the mighty wave of the Third Crusade had passed and his empire was intact.

Death & Legacy

Saladin was unable to profit from the Crusader's departure because he died soon after in Damascus on 4 March 1193. He was only 55 or 56 years old and most likely died from the sheer physical toll of decades spent on campaign. The fragile and often volatile Muslim coalition quickly disintegrated once their great leader had died, three of Saladin's sons each took control of Egypt, Damascus and Aleppo respectively while other relations and emirs squabbled for the remainders. Saladin did leave a lasting legacy as he founded the Ayyubid dynasty which ruled until 1250 in Egypt and 1260 in Syria, in both cases to be overthrown by the Mamluks. Saladin also left a legacy in literature, both Muslim and Christian. Indeed, it is somewhat ironic that the Muslim leader became one of the great exemplars of chivalry in 13th century European literature. Much has been written about the sultan during his own lifetime and since, but the fact that an appreciation for his diplomacy and leadership skills can be found in both contemporary Muslim and Christian sources would suggest that Saladin is indeed worthy of his position as one of the great medieval leaders.